Right Dorsal Colitis in Horses

by Heather Smith Thomas

Horses occasionally develop inflammation and ulceration of the gut lining, most commonly in the stomach (gastric ulcers). Colitis, or inflammation of the colon, is rarer, but can be very serious. For some reason, this problem tends to occur more in the right dorsal colon.

Dr. Anthony Blikslager, Professor of Equine Medicine and Surgery, College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, says that in his experience, right dorsal colitis is exclusively associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. “The only cases I’ve seen have been triggered by use of phenylbutazone. We don’t know why the right dorsal colon is affected and not the rest of it. One theory is that the colon contents (digested food moving through) are changing at that point near the end of the colon. The colon is doing less fermentation by then, and more absorption of water. This might mean it is concentrating something within the food or changing the microbial population,” he says.

“There is also debate whether there is change to the blood circulation (supplying the colon) at that point. Perhaps that part of the gut is predisposed to problems because it’s a bit more sensitive to changes in circulation. Prostaglandin (especially prostaglandin E2, or PGE2, which is thought to be protective in keeping the gut lining healthy) is inhibited by phenylbutazone. One of the things that PGE2 does is dilate blood vessels, under normal circumstances. Maybe the blood flow is a little less in the right dorsal colon (for some reason) than in other parts of the colon. Then if you remove prostaglandins (by using phenylbutazone) the crucial blood circulation to that area might become compromised.”

This would affect blood flow to the gut lining and hinder its mucus production. “The gut lining is very sensitive to changes in blood flow because of its high demand for oxygen, which helps energize the necessary enzymes and transporters. It can’t go without oxygen for very long,” explains Blikslager.

“Probably the ultimate scenario, regarding whether a horse might develop right dorsal colitis, would be a combination of factors. One factor would be the individual horse. If that horse is extremely stressed for some reason (which can change things in the gut), it might be more vulnerable to this problem. Each horse also has its own individual microbial population. Some will have a few more ‘bad bugs’ than other horses. Then when you add phenylbutazone into that picture, and it slightly reduces the blood flow to the gut, this might be enough to push that horse over the edge in terms of health of the lining,” he says.

This is a similar to what causes ulcers in humans. “In people, we used to think that ulcers were purely acid caused, related to diet. Now we understand that it is also related to individual factors, in certain people. It’s not just diet, although it plays a role. It’s also bacteria (particularly Helicobacter pylori). Problems in the gut are usually due to multiple factors. Inside the gut there is always a delicate interaction with the contents (food) and the lining, and the overall influence of the body on what’s going on in the gut,” he says.

“Fortunately, right dorsal colitis is rare in horses. It used to be thought that this disease was due to an overdose of bute, but this is not necessarily the case. It can also be caused by normal doses.” Many horses with arthritis that are on very low maintenance doses to keep them comfortable do just fine, but some horses can’t tolerate long-term bute administration.

“We once had a horse here in the hospital that had an elective orthopedic procedure and was put on bute pre-operatively and remained on bute post-operatively at correct dosing, and acutely developed right dorsal colitis. It was so severe that we lost that horse,” Blikslager says. This is an example of an unforeseen severe complication of phenylbutazone administration.

Most cases, however, are sub-acute and slower in progression. “Rather than developing colitis within the first 24 hours, it comes on more slowly--within about a 5-day period after being started on bute. There are many cases where it’s chronic. The horse has been on bute for days, weeks or months, then develops a problem,” he says.

“So, it can catch you off guard in two different ways. It can surprise you if it happens very quickly and you were not expecting it and haven’t had a chance to wean the horse off bute. Or it can happen in situations in which the horse is seemingly okay with bute and is on it for a long period of time—and suddenly there is some sort of change, and the horse develops this problem,” says Blikslager.

“We’re not telling people to avoid bute. It is the cheapest and most practical way to treat a horse with chronic arthritis, which affects a lot of horses. We simply advise horse owners about sensible dosing. This means giving the horse as little as possible (just enough to do the job and relieve discomfort) for as short a time as possible,” he explains.

“Veterinarians have been pretty good about their advice to clients. The upper end of the labeled dose is approximately two grams twice a day for an average size horse. We may give one dose at this level, but then suggest giving 1 gram twice a day to start with, and then wean down to 1 gram once a day as quickly as possible. For horses that stay on bute for maintenance soundness or pain control, another approach is to not necessarily give it every day. Give the horse a day off from it periodically. Essentially this would mean that during that day off, the prostaglandins could bounce back and restore the gut lining to health before the horse goes back on the bute again,” he says.

“With gastric ulcers (in the stomach, rather than so far back in the colon) there are other things you can combine for treatment, like antacids. With the colon, however, it is so far away from anything you can give the horse by mouth that it is difficult to protect it,” he explains.

“The right dorsal colon is at the very end of the colon before it turns across the abdomen as the transverse colon and then out through the small colon. The right dorsal colon and transverse colon is just before the fecal balls start forming as water is withdrawn from the contents, and feces are starting to firm up. Interestingly, this is the same place that sand collects in a sand impaction, or where you might find an enterolith.” This part of the tract seems to catch things that might otherwise move through.

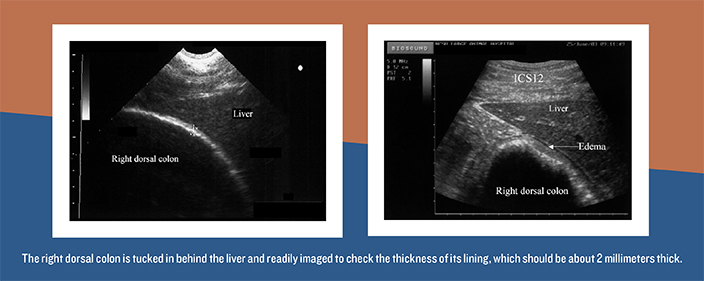

“We jokingly complain about the horse’s digestive tract being so convoluted and often talk about the pelvic flexure—and why would there be an area of colon with this hairpin turn. The right dorsal colon, by contrast, is not as tight a turn but it is still a bend, like going around a corner, from the right dorsal to the transverse colon. The good thing about where it is, however, is that it can be imaged with ultrasound. It has a fixed location, as opposed to much of the rest of the colon, which moves and is more variable.”

“The right dorsal colon can be consistently found near the 12th intercostal space (between those two ribs), tucked in behind the liver, and readily imaged. If we are using ultrasound--going up and down the 11th, 12th and 13th intercostal space with the probe and looking for the liver, we can then come off the back of the liver once we’ve located it and can find the right dorsal colon and check the thickness of its lining. Ordinarily it should be about 2 millimeters thick, and typically will have a little bit of gas in it. So just off the back of the liver you would see a bright line—the lining of the colon just before it becomes gas-filled,” he explains.

“Two millimeters or less would be normal, at that position, and anything more than that would be abnormal. You can see the mucosa with ultrasound and can tell when it’s thickened. For diagnosis, this can be a big help,” says Blikslager.

Diagnosis And Treatment

“Most cases can be a little difficult to pick up. Most horses with right dorsal colitis have only subtle signs. They won’t eat as much and look a bit depressed, and this might be about it, for signs.” The horse might be dull and possibly off feed. The owner may notice a change in the horse’s behavior. A subtle change might not seem significant but should not be ignored.

“It is important to have the veterinarian take a look. When examining the horse, they may not notice much that’s very definitive, so it is important to run some routine bloodwork. More than likely the horse might just look a little depressed and off feed, but we can check blood levels of protein. A biochemical panel will show the serum protein and the albumen, the most important protein for normal circulatory function. In addition, a CBC may show a low white blood count, specifically neutrophils. With these findings, I’d ask the owner more questions. From the history, we might learn that the horse was on bute,” says Blikslager.

This is always a very important part of the history, to ask what medications the horse has been on. “One problem, if a horse has been on bute for a long time, is the tendency to increase the dose when the horse is not feeling as good, which would be the wrong thing to do.

“If the bloodwork came back showing low protein and low neutrophil count, your veterinarian would either come back and ultrasound the horse or refer it to someone to ultrasound it. This would reveal the thickened gut lining, if the cause of these changes was right dorsal colitis,” he says.

“The interesting thing about ultrasound is that most veterinarians are comfortable using it to image the reproductive tract, tendons and other soft tissue structures, but not that comfortable imaging the abdomen. It’s not something they would typically do for a colic, for instance. But if they don’t feel comfortable doing it, they can send the horse to someone who does or call someone who knows more about it.

“If you have the history, with the horse being on bute and the subtle clinical signs, and then the bloodwork shows the protein is low, another way to go about it is just to start treatment. The immediate thing is to get the horse off bute and replace the PGE (prostaglandin E) that is needed. This can be done with a drug called Misoprostol which is just synthetic PGE1, very similar to PGE2” says Blikslager.

“It also helps to put the horse on a low residue diet (less bulk going through the compromised colon). This would mean a pelleted ration that is mostly digested before it reaches the right dorsal colon. This would help rest that area of the bowel. Veterinarians generally recommend doing this for up to 3 months. It’s a slow process, to heal the lining and get the protein level to come back up.” If the horse starts perking back up, moving in the right direction, this would be a sign that things are improving.

“The hard ones to deal with are the horses that keep deteriorating in spite of treatment. The colitis is literally an ulcer of the gut. Colitis implies inflammation, but when you actually look at the lining it will be thickened (and this is why you can see it with ultrasound). The thickening is due to a lot of inflammatory cells and some scar tissue starting to form. It is missing the vital inner lining of epithelium that protects the body from what’s inside the gut. Without this protection, the horse can become endotoxemic. If we lose the horse, usually it’s because of a combination of reduced protein and endotoxemia,” he says.

With some horses, the protein just keeps dropping and this is very frustrating to deal with. “We can give back protein in the form of plasma, but it is expensive to keep doing this.” At some point the horse has to stop losing protein or he won’t survive.

“This is similar to many other colic-type problems; if it comes on quickly, they are more difficult to save. If it comes on slowly, you have a much better chance of being able to get them back to health. The rapid ones (acute cases of right dorsal colitis) are probably due to a sudden loss of gut mucosa, and the resulting endotoxemia. Horses with right dorsal colitis have a guarded prognosis, which means less than 50% of them make it,” he says.

“Serious cases that come on suddenly might show fever and diarrhea. Others have more subtle signs, such as behavioral changes and going off feed. In a horse with fever and diarrhea, my first thought would be colitis affecting the whole colon. This is a medical emergency, and these horses are difficult to save because they lose so much fluid via the diarrhea.

“If the horse is systemically sick, there will also be some absorption of toxins into the bloodstream (endotoxin) and that will really complicate things. This would be an acute presentation, and not all cases will present with this.”

“Some veterinarians don’t use Misoprostol for treatment because it can cause horses to colic a little and they don’t feel comfortable with that. But in our hospital, in the cases we’ve treated, we’ve found that was an important part of what enabled us to get them back to health. We felt like the benefit of getting the prostaglandins back into the horse outweighed the concern about them getting crampy. We knew we could stop the drug or lower the dose if they did,” he explains.

Substitutes For Bute

There are other NSAIDs that can be used as alternatives to bute. “Bute is generally regarded as being good for treating musculoskeletal pain. The other drug labeled for osteoarthritis--and supposed to be safer for the gut--is Equioxx, but it’s a lot more expensive,” says Blikslager. Many people continue to use bute because it is cheap, and easy—putting the powder in grain, or mixed with water and molasses and squirted into the mouth if the horse won’t eat it in grain or using apple-flavored paste.

“Many people don’t even think about possible side effects of a drug like bute because it’s so commonly used, and most horses do fine with it. You can probably find it in just about every horse barn. But if people think about it and realize that not every person can take aspirin or Advil, they might understand how not all horses can tolerate bute,” he says.

“Because bute can have this side effect (and any NSAID can), there are newer NSAIDs on the market called COX2 inhibitors. The one that’s on the market for horses is Equioxx. This would be for something like arthritis (in which the horse is being treated continually) with the idea that it has a safer gut profile. In theory, this is true. It comes in a paste formulation for horses. The same drug in a canine formulation is called Previcox. It’s a small pill, and some horse owners are using this little pill rather than the more expensive Equioxx. The trouble is that this is off-label. When there is an FDA-approved formulation for the horse, you are not supposed to use the other,” he says.

Owners need to understand why some veterinarians are unlikely to sell them Previcox. This form has not been studied for safety and efficacy in horses. “If you use it and the horse has a problem that is thought to be related to the drug (such as any problem related to anti-inflammatory medication—like kidney, stomach or gut problem), this could be an issue. Equioxx is theoretically safer, but it is in the same class of drugs. If the owner were to complain about a problem with use of Previcox, the veterinarian wouldn’t have any support for that, and would get into trouble.”

“In many situations there are no drugs approved for horses and in those cases, we can use drugs that are off-label. But this happens to be a situation where there is an approved drug,” he says.

Case History Of A Horse With Right Dorsal Colitis

In September 2013, Debra Stoltz (a horsewoman in Fort Lauderdale, Florida) purchased a two-year-old gelding, Mister Cool Jet (nickname Cooper). His first year of training went well, and then in October 2014 Debra noticed a change in his attitude.

“Cooper became cranky, and his coat was dull. We changed his feed and supplements, floated his teeth, and gave him two weeks off with just turnout, thinking he was exhibiting signs of stress,” she says.

Cooper was put back into training in mid-November but continued to be “off” and not his usual happy self. Debra noticed that the horse was now very sensitive to right leg cues and pressure when ridden.

In late December, he went lame and was treated with low dose bute for 5 days. “Then on December 31, I received a call from the barn manager telling me that Cooper was lying down in his stall, not eating, and running a fever. By January 4 he had diarrhea, so he was rushed to Palm Beach Equine hospital, where the initial diagnosis was colitis. Ultrasound later confirmed that his colon was enlarged, and he had right dorsal colon ulcers,” says Debra.

The horse was given fluids and plasma, since a blood test showed that his protein level was very low. A catheter was inserted into his jugular vein to administer the fluids, but it collapsed, and the opposite vein was used.

Further treatment included gastrogard paste and sucralfate for ulcers, Misoprostol (a synthetic prostaglandin), metronidazole (an antimicrobial drug) and a probiotic, in an attempt to help his gut function, get back to normal. Cooper was discharged from the hospital after 4 days on these drugs.

“Later that same night, I checked on Cooper and noticed that his head and neck were significantly swollen. He was rushed back to Palm Beach Equine where the diagnosis was thrombophlebitis (blockage by a blood clot) of the right jugular vein. He was treated with mesotherapy (injection of medications into the subcutaneous tissue with tiny needles), and the veterinarians assured me that he would show signs of improvement by morning. During the night, however, the left vein also became blocked. The right vein was 100% occluded and the left was 50 to 60% occluded,” Debra recalls.

“They treated him for 4 days with heparin (an anticoagulant), buffered aspirin, Excede (an antibiotic) injections and pentoxifylline (a drug used for improving blood flow). He was released from the hospital and was kept on this new drug regimen along with the previous protocol for colon ulcers but continued to have head/neck swelling and low blood protein levels. The recommended diet was 1 quart of senior feed 4 times a day and 4 flakes of hay daily with at least one flake being alfalfa,” she says.

On January 17, just 4 days after coming home from the hospital, Cooper suffered severe colic and was referred to Dr. Meg Miller Turpin. “She instructed us to bring him to Reid Clinic in Palm Beach. He was immediately diagnosed with internal bleeding, likely from the heparin and aspirin, which was immediately discontinued. He remained on ulcer medications but continued to have colic episodes one to three times per week, along with diarrhea and continued edema of his head/neck and sheath for about 4 weeks,” says Debra.

During this time, DMSO and hot packs were applied to the blocked jugular veins, and Dr. Miller recommended treatments in the hyperbaric oxygen chamber to increase and improve blood circulation to aid the healing process. Cooper received 5 treatments in the hyperbaric chamber. His diet was senior feed 4 times daily, and one feeding (5 pounds) of alfalfa daily.

He showed no significant improvement by early February and was started on probiotics. His grazing time was limited to 1 hour per day to limit the amount of time his head was down, since having his head low accentuated the swelling from the blocked veins. He was given 4 more treatments in the hyperbaric chamber.

On February 21 he was finally discharged from the clinic but was still physically compromised. His blood protein levels were the lowest ever and his hair had started to fall out. Dr. Miller submitted blood samples to Kansas State University and the results led her to suspect something like AIDS or lymphoma. The good news was some improvement in blood flow through his compromised jugular veins. He continued on with ulcer medication and the same feeding regime and was gradually allowed to graze up to 2 hours per day.

He remained relatively stable until another colic episode on March 11. The next day he was taken back to the Reid Clinic and Dr. Miller performed a biopsy and stomach scope, which ruled out AIDS or lymphoma. Protein levels were slightly improved, and his hair was growing back in. He was taken off hay completely (since fiber has to be digested in the hindgut) and his senior feed ration was increased to 16 quarts daily. He was discharged from the clinic on March 22.

Blood tests the end of April showed more improvement, and he was given a good prognosis for leading a normal life. Dr. Miller recommended that he should never be given bute again, and also said his jugular veins would never be suitable for injections.

The bute he was on in early December essentially set him up for problems on both counts (the right dorsal colitis, and the jugular vein thrombosis). Sometimes when a horse is on NSAIDs it will suppress clotting, and then when you take the horse off those drugs there is almost a rebound effect that stimulates clotting.

Debra was relieved to have her horse healthy again. “I felt extremely lucky, because there were a few times we didn’t think Cooper would pull through. At one point I was told that he would have to be prevented from grazing because he could never be allowed to drop his head for more than an hour.” Fortunately, the blocked veins resolved, and he also overcame the damage in his colon. Debra feels that youth was in his favor, along with the excellent care from Dr. Miller.