The Man On The Hill Part 1 On The Road To Stars And Beggars

In the springtime of 1928, a slim man of medium build with blue eyes secured enough cash to acquire 240 acres of land in the Osage Hills of northeastern Oklahoma. Against the advice of friends who feared the rumbles in the national economy and suggested waiting until times were safer, the man and his wife, and their two daughters, set up housekeeping on the spread between Nowata and Bartlesville the following year. Electricity and plumbing were lost items. The only available water was pumped from a small well.

The man christened the spread Cross J Ranch. He was determined to build it into a haven for sleek Herefords, but – above all – he envisioned the Cross J brand on the thighs of the rodeo and race horses he dreamed of breeding.

As the years unfolded, the Cross J evolved into a four-thousand acre spread of bermuda and bluestem. A majestic, two-story home made of native stone from Cross J land dominated a hill. The man behind the Cross J brand designed the house, reserving the first floor for comfortable dens and offices. Bedrooms, living rooms, kitchens, etcetera, were up there on the second floor out of his way.

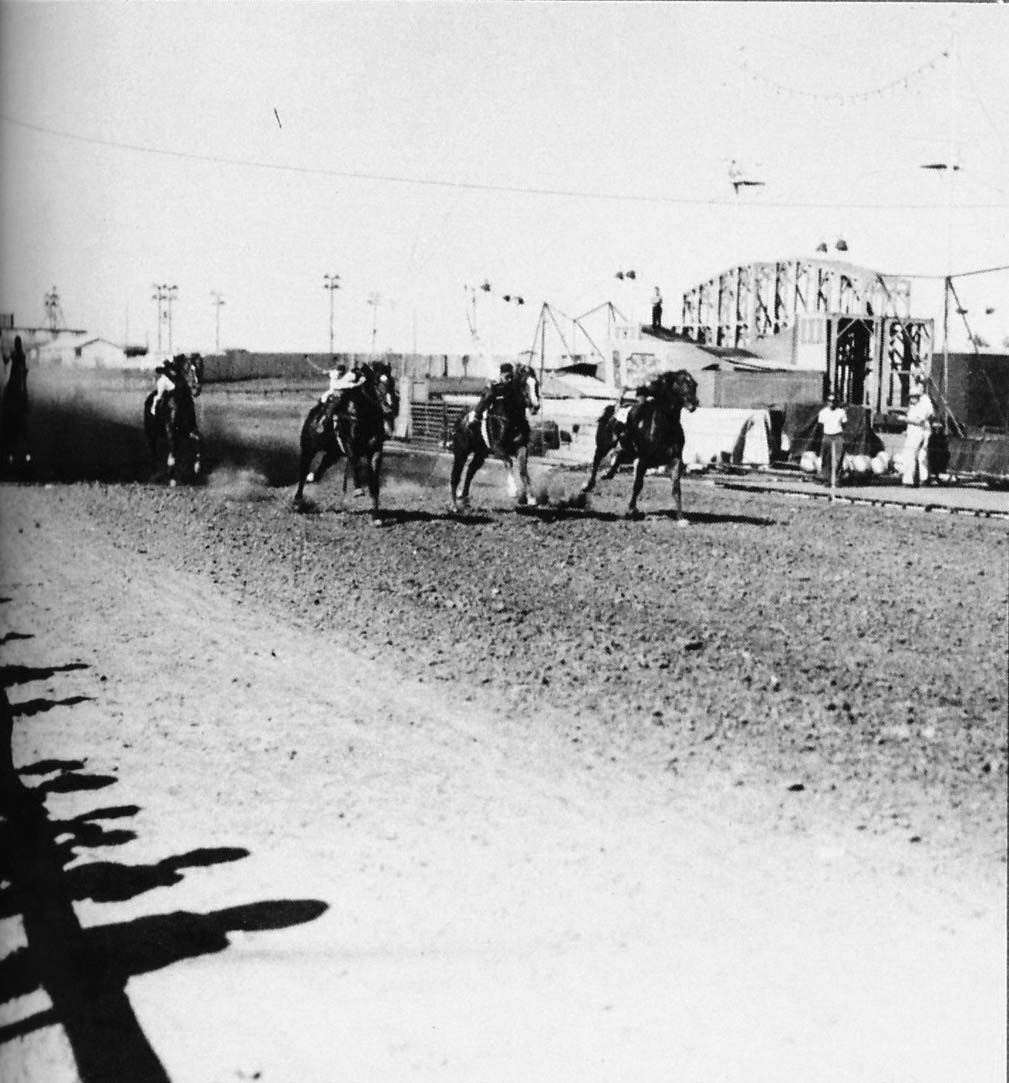

Decade by decade, the horses that left home with the Cross J brand on their thighs would, briefly put, blind the souls of many strong men and women to all but Cross J blood. Quarter Horse breeders deemed it the magic potion to strengthen their programs. Straightaway addicts chased it. Rodeo greats contracted for Cross J foals still in their mammas’ bellies. At the same time, Cross J Thoroughbreds caused some ripples in the purple-bred set by lowering a few records for a mile or more east of the Mississippi and south of the Rio Grande.

Some of the Thoroughbreds that left the Cross J were progeny of the black stallion from Oklahoma that could finish a quarter in :21.6, but lost momentum beyond that pole and could never be rated in Thoroughbred circles. Beggar Boy. This was the stallion whose blood the man behind the Cross J brand chose to cross on to the daughters of the mahogany bay with a star and a left hind sock, Oklahoma Star.

Oklahoma Star and Beggar Boy were marked for greatness, and they achieved it – singly at first and then together on the Cross J. Their blood, separate and blended, did as much as any and much more than most to revitalize the “zing” of the frontier horses that became the backbone of AQHA foundation stock.

Beggar Boy and Oklahoma Star proved to be of such mettle that their names, inserted into any conversation among horsemen of that era, could upstage anything – even other Cross J horses. Consequently, many of the Cross J greats ran second to the romance, the legend, and the fact of Star and Beggar.

Today the man behind the Cross J brand – Ronald S. “Ron” Mason – is going on ninety-one. Ron and his second wife, Monett, live in a long, low, white house on a hill overlooking the golf course west of Nowata, Oklahoma.

Monett lights a fire in the big, stone fireplace in the living room at dawn on chilly mornings and turns on a few lamps that send a glow to all the horse photos and paintings lining the wall. About the same time blades of sunlight replace the lamplight in the living room, Ron appears. He is as slim as he ever was. His legs and back bother him on occasion, but he will not bend to them.

“I never killed anybody or ran off with another man’s wife or made a dishonest nickel off of anybody. Now I might have sold a horse too high on occasion, but for every one I sold too high, I sold lots of others too low.

“The one thing I always wanted to do, and never did, was take my horses all the way, to the track or wherever. I was always too involved in running the ranch, and in other pursuits, too. A man can’t do it all.

“When AQHA started up in 1940, a lot of people started telling me I was messing things up by keeping on with Thoroughbred infusions. I told ‘em to go to hell. It takes a Thoroughbred, the RIGHT Thoroughbred, to make a good Quarter Horse, it’s as simple as that. I’ve had too doggone many horses to remember all of ‘em, but just a few of the Thoroughbreds I’m thinking about right now are Sun Pharos, Busy Deck, Catwalk, Sea Dog, Swift Abbey, Ginger Brown – I mean there was a slew of ‘em. Some were bred to Quarter Horses, some weren’t.

“Take Catwalk – he was ever so slightly parrot-mouthed, but what the hell. He was a chestnut foaled in 1930, by Wildair by Broomstick and out of Verdure by Peter Pan, and through Peter Pan, of course, you’re swinging over into Peter’s son, Black Toney, the sire of my Beggar Boy . . . I’ve always been a man who wanted to seek and to know, and there’s many a time when I’ve studied pedigrees all night and all day, looking hard as I could for some secret, some clue as to what made the horses so great.

“What is a Quarter Horse, anyway? They told me it was a horse that could consume the quarter faster than any other breed. But, I’ve known Thoroughbreds that could do it consistently in twenty-two seconds flat – or less.

“Just because a man thinks he knows his horses better than anybody else doesn’t mean he does. Like, I once gave a Thoroughbred away because I thought he was too runty to do anything. Sugar Brier, was his name. I gave him to Pete Durfey. They went east, and the first thing I know is that the colt’s entered in a race at Churchill Downs. Pete calls and says I ought to lay some money on Sugar Brier, but I wasn’t about to.

“Sugar Brier goes off the board with the kind of odds that can embarrass the man that bred him. But, then he cuts loose and goes six furlongs in 1:13 3/5, and a $2 win ticket on him pays $101.40. Now that was in November of 1954, and Sugar Brier went on to collect some more notable wins, too . . . if I gave the colt away, it all came back to me in the end. Pete always kept me informed about what was going on at tracks I couldn’t get to.

“Sugar Brier goes off the board with the kind of odds that can embarrass the man that bred him. But, then he cuts loose and goes six furlongs in 1:13 3/5, and a $2 win ticket on him pays $101.40. Now that was in November of 1954, and Sugar Brier went on to collect some more notable wins, too . . . if I gave the colt away, it all came back to me in the end. Pete always kept me informed about what was going on at tracks I couldn’t get to.

“Oh – I forgot to tell you when I was talking about Catwalk that he had this Thoroughbred daughter, Fine Girl, and she foaled six running horse winners. One of ‘em was Nowata Dumpy, he being heavy Oklahoma Star on top through his sire, Double Star. Dumpy was another one I misjudged. I judged him hopeless because he was so close to the ground. So, I named him Nowata Dumpy. Well, he turned into another kind of vehicle when he left the straightaway gate. He won fifteen straight. He looked like a jackrabbit when he ran, but you forgot all about that peculiarity when you looked at the daylight he built behind.

“They say there’s a time to buy and a time to sell. But, some come along. Some came along that I didn’t want to sell, and wouldn’t. I had this Thoroughbred colt, Beggar’s Lad by Beggar Boy out of a little mare from England, Lad’s Run. Carl Hanford came out to the Cross J, and he really liked Beggar’s Lad and wanted to buy him, but I wouldn’t sell. I guess that kinda changed history a little, because Carl went on back east and ended up training the great Kelso.

“It’s been almost fifty years since people started asking me which one I thought was best, Oklahoma Star or Beggar Boy. Questions like that always make me tired. All I can say is that Beggar could do anything Star could do, but Star had the name. Both studs had real good dispositions, they were something to behold. Some of the men who worked for me back then told me they were convinced that Star talked with his eyes, and that they were convinced that he knew what was being said to him. I just can’t go that far. Beggar Boy, good-dispositioned as he was, could get uppity on occasion.

“All I can say is that Oklahoma Star and Beggar Boy were horses in their own right before I got ‘em. And I’ll say this – once I got ‘em, regardless of all the times, all the chances I had to sell ‘em, I’d have soon as sold myself.

“A lot of bull has come down about Oklahoma Star’s dam. I’ll get to that later. What I saw in Star was his topline, going through his sire Dennis Reed – he was quite a speedster himself – being by Lobos by Golden Garter by Bend Or.

“After a lot of years, I came to the conclusion that Star’s dam, Cutthroat, was in truth the daughter of the Thoroughbred Bonnie Joe. Bonnie Joe also happened to be the sire of Uncle Jimmy Gray and Joe Blair and Useeit, the dam of Beggar Boy, and his blood brother, the 1924 Kentucky Derby winner, Black Gold.

“To me the letters of a pedigree on paper make a kind of music that only fools ignore. Like I fell in love with the Thoroughbred Discovery. Who didn’t? He was a chestnut foaled in 1931 – by Display by Fair Play and out of Ariadne by the imported Light Brigade by Picton out of Bridge Of Sighs by Isinglass by Isonomy. If you ever wonder how I can remember all those names, it’s because I pored over Discovery’s bloodlines for so long.

“See, I always wondered what made Discovery as great as he was – on the track, in the stud, as a maternal grandsire. I finally decided it might be because he had a double dose of Insonomy in him. It comes through Light Brigade. Light Brigade’s dam, Bridge Of Sighs, was by Isinglass by Insonomy. Light Brigade’s sire, Picton, was out of Hecuba, also being by Insonomy.

“So, if you hold the way I do, that Star’s and Beggar’s maternal grandsire was one and the same, Bonnie Joe, well that put a double dose of Bonnie Joe into all the pedigrees of crosses between Star and Beggar.

“Two foaling dates come down for Oklahoma Star. One’s in May 1916. I hold with the one

that’s April 12, 1915. So, by my calculation, Star was seventeen years old when I bought

him out of a calf lot in 1932 – that’s where I found him – in a calf lot. He hadn’t been off the track too long. I hear tell that, give or take a little, he was on the track for a dozen years or more.

“As for Beggar Boy, he stood there with his owner, Widow Hoots, in Oklahoma. I bred some mares to him, but never ever dreamed that the widow might consider selling him. In fact, I think it was 1938, and Beggar Boy was fourteen years old when I went out there to talk to Widow Hoots about breeding a mare to her horse. In the process of the conversation, I learned she was into a deal whereby she might sell Beggar Boy to some Texans for two thousand dollars. Well, I almost fell down when I heard that. I had two hundred dollars cash in my pocket and asked if she’d take it and I’d come back with the rest the next day.

“As for Beggar Boy, he stood there with his owner, Widow Hoots, in Oklahoma. I bred some mares to him, but never ever dreamed that the widow might consider selling him. In fact, I think it was 1938, and Beggar Boy was fourteen years old when I went out there to talk to Widow Hoots about breeding a mare to her horse. In the process of the conversation, I learned she was into a deal whereby she might sell Beggar Boy to some Texans for two thousand dollars. Well, I almost fell down when I heard that. I had two hundred dollars cash in my pocket and asked if she’d take it and I’d come back with the rest the next day.

“That’s how I got Beggar Boy.

“That was one time when the Texans were just a little slow on trigger.

“There’s the picture of a horse here on my wall that I’d never let anybody take away. I guess he went as far as anything walking to show what a Star-Beggar cross could do, but you can’t leave his sire, Chicaro Bill, out of it, either.

“I bred that horse in that picture on the wall. I bred his mother and his maternal grandmother. His grandmother was Peaches by Oklahoma Star out of J4. J4 was this mare I got from Will Rogers’ nephew, Herb McSpadden. J4 was by Old Red Buck out of a bay mare by Red Man.

“Then I bred Peaches to Beggar Boy and got a black filly with a slanting star. When she was full-grown, she was 14.2 and weighed around 950. I named her Beggar’s Peaches. Her name went onto the list of all-time leading producers in AQHA, and it’s still there.

(Beggar’s Peaches is “Little Peach” on AQHA books.)

“I honestly don’t remember if it was before or after I acquired Chicaro Bill, but I bred Beggar’s Peaches to Chicaro Bill and got Bill Doolin in 1944.

“I honestly don’t remember if it was before or after I acquired Chicaro Bill, but I bred Beggar’s Peaches to Chicaro Bill and got Bill Doolin in 1944.

“Bill Doolin was as good an example of one hundred percent TRY as has ever breathed air. A lot of good men wound up going soft over Bill Doolin – I hear that he turned Bill Hedge’s life around, in fact.

“Bill Doolin wasn’t just as racehorse, he was some sire and some maternal grandsire. One of his daughters, Monett Mason, named after my wife, is a leading producer in AQHA computers.

“That horse in the picture there on my wall – Bill Doolin – they say he was lucky because after I sold him, all the owners he had were good to him. Luck didn’t have anything to do with it. You get what you give in this life, and Bill Doolin got his.

“. . . I’ve always said that anybody that got past the age of eighty oughta be knocked in the head. But I’m still here. A long time ago, I almost went into professional boxing. They say I had a good left jab. I’d be willing to try and prove I had it if anybody came up to me and said anything unkind about Bill Doolin.

“I was full of fire when I bought the 240 acres back in ’29, and by the early thirties, I was into breeding horses like I wanted to be. People start associating me with horses about that time, but breeding good horses was something I always wanted to do. It just took me a while to get down to it.”

In 1896, Ron was five years old and still living in the state where he was born, Ohio. His grandfather was a doctor who depended on a horse and buggy team to make housecalls in emergency situations or otherwise. He demanded the best of horses.

“My grandfather had a measuring stick behind his eyes. He could have taken one look at a horse, then gone off, made a skin-tight coat, and it would have been a perfect fit on the horse. It was through him that I first learned the difference between horse and HORSE.”

In 1905, when Ron was fourteen, his father was in financial trouble and took a longshot. He hauled his family south to the settlement of Nowata in Indian Territory to begin a new life.

“My father set up an abstract company in Nowata, handling court records and documents, things like that. He built himself back up again, and we fared pretty well. I had a brother, Charlie, that I loved a lot. He was sorta the family pet. Down the line, he took a little financial help from our parents, and Charlie ended up being Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma. As for me, I never asked for a dime from anybody.”

Ron finished high school in Nowata in 1907, the year that Oklahoma became the 45th state in the union. By then, he was somewhat of a scrapper who seldom began a fight but had the reputation of putting an abrupt ending to one, in his favor. For a while, he fought professionally and was gaining a name for himself among the pros when he made the decision to hang up his gloves.

“Fighting wasn’t really what I wanted to do.”

By 1909, Ron was hoeing corn for fifty cents a day in Nowata. He eventually migrated to East Texas and hired on with an oil company, dressing tools. His daily wages skyrocketed from fifty cents to eight dollars. By 1919, he had progressed from dressing tools in East Texas to buying and selling oil leases for Sinclair Oil Company in North Texas. He remained in that pursuit on a fulltime basis until 1928. During that period, his path crossed those made by two other men. One was Langford Shaw, who also bought and sold leases.

“We became lifetime friends. I named my first son after Langford. He was never involved in horses with me in any way, but I wouldn’t want this story written without mentioning his name.”

The other man whose trail crossed Ron’s was Clarence W. Wright, a self-made man who had entered the business world while still in his teens.

“I started out hoeing corn, and he started out with a steam popcorn machine. How about that . . .”

At the time Ron Mason and Clarence Wright met, Wright was an original investor in the petroleum company, Sunray DX, and was a director and vice president of the company. Sunray had been in operation for several years, but not on a bigtime basis. Then in 1928, Ron came across some property north of the Canadian River.

“It could be had for one million flat, no small sum in those days. It was ripe, just right for Sunray. So, I called Clarence Wright and told him I wasn’t asking, I was telling him he had to buy it. He did.”

Ron’s commission on the $1 million deal was 5%. It was confirmed in writing in the springtime of 1928.

“Right after that, I went looking for land of my own and found the 240 acres. I was living in Tulsa at the time. Clarence Wright wanted me to stay in oil, and if I had, I could’ve been a millionaire, I guess, like he turned out to be. But I finally had the money to get into horses, and my mind was made up that that’s what I was going to do.

“Clarence Wright and I never lost touch with each other. The lease I negotiated for him turned Sunray from a fledgling into a big bird in oil, and Wright never failed to tell me so. So, I guess that lease north of the Canadian River turned both our lives around.”

Sunray DX, after drilling successfully ahead for many years, was finally purchased by Sun Oil. One of the last personal letters Wright penned before his death was a warm note to Ron Mason, who keeps that note, along with correspondence from Langford Shaw, also deceased, in a special scrapbook. In that same scrapbook, there is a section devoted to another individual – a lengthy photo layout showing a big range horse in various poses. Cutlines in Ron’s script: “Big Red.” “Big Red, My Using Horse.” And one, with Ron aboard – “Big Red and Me.” On and on, one man’s tribute to the horse that was friend and transportation during the heyday of the Cross J.

Big Red descended from the family of Blake Horses, as did many mares that can be considered among the foundation mares of the Cross J. The Blake Horses were bred to the ideal standards of their breeder, Coke Blake, of Pryor, Oklahoma. Around 1878, Coke Blake first glimpsed a dark sorrel in the land of the Daltons, Younger and James brothers. The owner of this fast horse, Foss Barker, tacked up a special sign wherever the sorrel was stalled – “Cold Deck Against the World.”

It was Cold Deck’s destiny to live and breed and race in the midwest and southwest when hell and lies were raised every day. Whether he was by Steel Dust or by Steel Dust’s son, Old Billy, is anyone’s guess. His mother was Maudy by Bay Cold Deck by Hamburg Dick by Printer I by Janus II by the imported Janus, if common accord among Quarter Horse historians can be considered unerrant.

Cold Deck sired many fast sons and daughters. Four of his sons – Diamond Deck, Grey Cold Deck, Printer II and Berry’s Cold Deck - established strains and families through which the thundering runs of Old Cold Deck would forever echo.

Old Cold Deck became Coke Blake’s ideal, and Blake began his famous family of horses (his desire was to breed all-round horses that could do anything) with the help of Cold Deck’s son Berry’s Cold Deck, and representatives from three other strains – Brimmer, Bertrand and White Lightning. These White Lightning actually descended from Brimmer and Bertrand strains. They were primarily gray horses, 15 handers, weighing about 1300 pounds, hard to beat for 300 yards.

On record is the story of a shootout between Jack Alsup, one of the three brothers who created the White Lightning strain in Tennessee. Seems the Alsup brothers finally sold their horses and left Tennessee. Then Jack reappeared with the objective of acquiring a White Lightning, probably on his own terms. Anyway, the sheriff was shot, and Jack headed out with White Lightning. A posse was subsequently formed to round up the Alsup brothers. Shelp and Lock were killed, but Jack survived and still had the White Lightning. Somewhere on the edge of it all, Coke Blake acquired four White Lightnings in Oklahoma.

Time consumes everything, even the greats. By 1903, Berry’s Cold Deck was aging but still breeding strong. During that same year his special son, Tubal Cain, was foaled by Lucy Maxwell, a White Lightning by Alsup’s Red Buck. The story comes down that Coke Blake chose Tubal Cain to replace his sire as chief stud when he heard the stallion make a sound like low thunder when he shook himself.

A significant number of horses counted in Cross J foundation stock were linked to Cold Deck and Blake horses through John Dawson’s stallion Old Red Buck by Red Man by Tubal Cain, and out of Pet Dawson out of Babe Dawson – this mother/daughter team linked to Cold Deck through Babe’s sire Little Earl.

Such was the foundation blood that awaited the mahogany bay, Oklahoma Star, when Ron Mason bought him out of a calf lot in 1932. Star, sixteen or seventeen at the time, had logged more than a dozen years on brush tracks. He had sons and daughters everywhere. But most of those would not make it into the AQHA of the future. Most remained unknown, except to those who owned them.

Something wonderful seems to happen when a good man and a good horse get together. The partnership of Oklahoma Star and Ron Mason was no exception. The man gave the stallion the best mares he could provide, and the stallion took it from there. In just a few short years, the black horse moved in, and no one will deny that Beggar Boy knew what to do with Oklahoma Star mares.

Part 2 will appear next week